BONHOEFFER A PERSON FOR OUR TIMES (Post 3)

On the danger of starting with creation when you’re trying to resist the Nazi’s

Warning: This post gets into the deep weeds of Christian theological ethics and formation.

This is the 3rd of 5 posts on ‘Fitch’s Provocations’ addressing Bonhoeffer’s theology for our times. Bonhoeffer is a Christian model for how to live in the current political ideological climate. Bonhoeffer’s theology formed him, shaped him for giving an unrelenting witness to Jesus amidst the Nazis even unto death. For this reason, his theology is worth examining because we all need this kind of theological formation for the ideological times we live in.

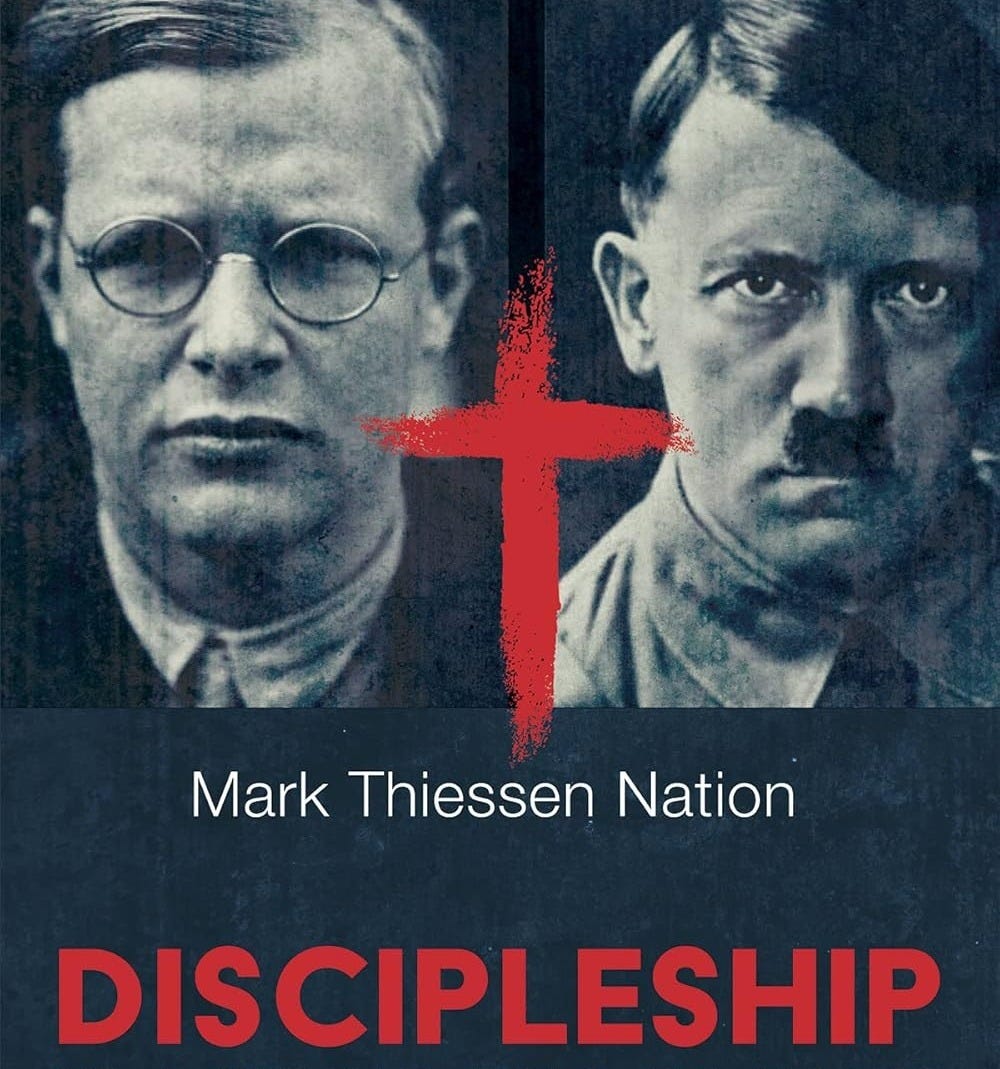

I’m drawing entirely from Mark Thiessen Nation’s book Discipleship in a World Full of Nazis whose book traces Bonhoeffer’s theology alongside the events of his life. It’s a powerful exploration of how theology forms a life of witness. After reading it, I’m convinced if there’d been a few thousand more Bonhoeffers as pastors and a few thousand more Finkenwaldes (the learning community Bonhoeffer planted) in Germany in the thirties, Hitler never would have happened. Perhaps the same can be true for our time?

Creation as The Foundation for Moral Living

The role of “creation” in one’s ‘ethics’ is the subject of this post. What is your theology of creation? What role does creation play in the way you make moral judgements? (We spend much time on this subject in Northern’s MATM program). Bonhoeffer helps us sort out the importance of this question for our moral lives, and our engagement with the state, as he himself faces the Nazi culture. He hears all around him the mantra that God has created in us (the German Volk) a superior people! In sorting this out back then, Bonhoeffer helps us sort it out today for the ideological times we’re living in.

The notion that God has created all things good is prevalent among modern Christians. It sets the foundation for many of our most basic moral decisions in evangelicalism and post-evangelicalism. It starts with Genesis ch. 1 and affirms that I am created good in God’s image. This includes a set of embodied goods, my abilities and gifts, my desires, sexual and otherwise. These all are all created good. This recognition can then endorse all of these created ‘things’ as good.

This is all ‘good’ (see what I did there?). In the post-evangelical world, this affirmation has served as a corrective to the evangelical fundamentalist Reformed-ish focus on the sinful depravity of human beings and their emphasis on the loathsome sinful state of human beings. To evangelicals brought up to believe (in the words of Martin Luther) “I am nothing but a filthy, stinking bag of worms,” this is welcome news . Romans 3:23, “we have all sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” gets balanced by Genesis 1:31, that God has created all things and declares that it was good.

This goes along with the mantra of many rebounding from evangelical fundamentalism. They suggest that for too long we have started our ethics with Genesis 3 (the fall) and forgot Gen 1. There is some merit to this. This appeals especially to a culture that focuses on the therapeutic. There are psychological negative effects to making “you are depraved” the starting point for your relationship with God. So agreed, we must not forget that we are created good, that the earth is created good, in our moral theology.

But this does not do away with the reality of sin. We live in an incredibly broken world. The affirmation that we were created good does not do away with the reality that creation has been corrupted by sin, death and evil. And so there can be no easy direct access to pure creation. We must discern between what is good in creation and what has been tainted by sin. We need a way back to the goodness of creation, a way to enter afresh into the ongoing purposes God created all things with in the first place. For Christians, this is Jesus.

What Can Go Wrong With The “Created Good” Ethic?

Like I already said, when creation, and I mean stand-alone creation, becomes the go-to foundation for our moral lives, everything can get affirmed as created good. And this seeps into our everyday lives.

I once heard a sermon at a mega church about how God has created us for fulfilment in our jobs. Every person therefore deserves a job in which they are fulfilled in. We were created for this! As I stood in the foyer, greeting people as they left the sanctuary, everyone walked out disgruntled about their jobs. I left pondering, “are not our desires something we grow in? Do we not grow in sanctification as we do work worth doing for others?”

I once heard Joel Osteen describe how he and his wife would take walks in the evening passing by glorious mansions in Houston neighborhoods, and they would say God has created in us a desire for success and a big house like this. But is this God’s created goodness? Gigantic material wealth?

This same logic has been applied among evangelicals to affirm toxic masculinity, “trad wives,” and by progressive evangelicals to affirm alternative sexualities, gender types. We were created this way, created good, in all our desires. In the process, we let slip reflection upon these desires, where they got formed, from where are they grounded, are they connected to sinful places like lust, greed, power, or selfish narcissism, and ultimately, how does Jesus shape our gender relations, sexuality, etc.?

Orders of Creation and Social Formation

This approach to creation and ethics historically has been applied beyond personal ethics into the social political realm. We say God has created government as good and therefore its functions are justified as positive goods to be conducted in line with God’s created intent. God has created us for family, business, the arts, etc. These are all created goods. Therefore, Christians should be emboldened to take up positions in all these human orders to fulfill God’s created goodness. Sounds “good” right? But what if these orders of creation reify toxic forms of family, masculinity, narcissistic self-focus, abuse of power as part of the very construct?

This approach to creation and ethics plays out in various traditions. Kuyper, and Dutch Calvinism, explained the various callings of life – government, business, family, education, etc, in terms of sphere sovereignty. Each one on these social orders was created by God with a created logic unto its own. Christians and non Christians alike can work together for the good of these spheres without a particular knowledge or allegiance to Jesus.

I have written about the problematics inherent to this way of thinking social ethics. For me, aligning worldly power with God’s purposes in created spheres lead s eventually to Jerry Falwell all over again. ‘The Seven Mountains’ theology of social engagement, that has driven many Christian’s alliance with Trump, has its origins with the spheres as some of these leaders were influenced by this Neo-Calvinist theology, albeit a misappropriation of it (which many of my Dutch Calvinist friends would be quick to point out). (Read Matthew Taylor’s book, ch. 5 on this muddled history)

Within more classic Reformed theological traditions, the distinction is made between orders of preservation and orders of creation. Orders, much like spheres, are social ordinances like government, family, education, business, and even church. If an order is preservatory however, it is a post-fall development, ordained to rein in the powers of sin and preserve society from falling apart in chaos from the forces of evil. If an order is created, it existed before the fall. It was created as good, for good purposes, and the goal of every Christian should be to work for its fulfilment of its purposes as good. This is more in cinq with the Spheres of Dutch Calvinism (I outlined these distinctions in Reckoning With Power, chapter 4)

If government is an order of preservation, government exists only to preserve society from the effects of sin, not redeem society. If government is an order of creation, created by God for goodness before the fall, we as Christians are called to work for the restoration of its goodness, inherent to its created purposes. We see the state differently. Instead of keeping the redemptive work of Christ in the world separate from the preservatory work ordained by God through institutions, we blur the two. The next thing you know, we’re baptizing certain agendas and certain legislative goals as part of God’s plan for what the government was created to do. It can get complicated. See Emil Brunner, The Divine Imperative, (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1937) on this, and the debate between Brunner and Barth on these avenues in Emil Brunner and Karl Barth, Natural Theology, trans. Peter Fraenkal (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2002).

All this to say, this is where Bonhoeffer comes in. In 1932, Bonhoeffer gave an address entitled “On the Theological Foundation for the Work of the World Alliance” at the meetings of World Alliance in Czechoslovakia. Thiessen-Nation refers to it in his book on page 67. In the address, Bonhoeffer offers a stern critique of the notion of the “order of creation.” He says that there lies a “special danger” in this idea. He describes this danger in terms of “basically everything can be justified on its basis. One need only portray something that exists as willed and created by God, and then everything is justified for eternity: the strife among peoples of humanity, national struggle, war, class distinctions, the exploitation of the weak among the strong, economic competition as a matter of life and death.” Bonhoeffer says the fundamental mistake here is that this view does not take seriously the ways in which sin has affected everything that exists. Reggie Williams in his book on Bonhoeffer goes into a riff on how “created orders” worked in Germany to uphold the Hitler regime. See my review of it HERE.

How the Category of ‘Creation’ Can Go Off The Rails

It really is mind blowing how “creation-based social ethics” can go off the rails as be used to justify all sorts of political, social and personal moral behavior. Emil Brunner critiqued his contemporary Lutheran theologian Paul Althaus’s view of coercive force as natural to the created order. Althaus believed that “conflict of aims” are inherent to “the natural variety of the created order.” For Brunner, however, “where conflict exists which will only yield to force, there is sin, and not the divine creation” (p. 683 in Divine Imperative). Althaus ended up becoming a supporter of Hitler. Creation-based ethics paved the way for this?

Stephen Wolfe in The Case for Christian Nationalism (Moscow, ID: Canon, 2022) affirms the distinction between the powers of the church and the civil government. (104, 299-300). But then goes on to say that because the government is “natural, human and universal,” implying they are given via creation, government is “for the people of God.”(346). The church should therefore “pray that God would raise up [a Christian prince] from among us: one who would suppress the enemies of God and elevate his people” (323). Wolfe seems to justify the use of the state to impose Christianity (Christian Nationalism) upon a people because it is ”natural”, inscribed in the very nature of being human. Creation-based ethics paved the way for this?

Cornel West goes into detail how “natural history”, empiricism, “this is the way things are”, was used to justify racism in the history of the West. It’s not exactly “orders of creation” language but follows the same logic. (See his most famous piece on this “Genealogy of Modern Racism”). Judith Butler showed how culture naturalizes gender specifics and sexuality in regard to heterosexual misogyny and patriarchy in Gender Trouble and other of her earlier writings. The logic of “this is the way things are, i.e. created” (what she calls ‘naturalization’) is used to justify certain modes of heterosexual gender and sexuality that she deems fraught with power and abuse.

All of this shows the many ways the creation logic can be used to justify the most basic moral understandings of the way we live. Indeed the creation logic, “this is the way things are,” “this is the way we were created,” is the go to justifications of those in worldly power and privilege to justify the things they do in the name of God. In these ideological times, it is therefore extremely important to become discerning Christians in how we use creation to ground our theology and moral discernments.

Bonhoeffer’s Challenge to Us Today

In that same 1932 lecture to the World Alliance mentioned above, Bonhoeffer goes on to say “From Christ alone we must know what we should do… from him who gives us life and forgiveness… (in this life) we are wholly directed toward Christ. Through this … we understand the entire world order of the fallen creation as directed only toward Christ through the new creation …” Bonhoeffer then explicitly sayss that “the value” inherent to God’s orders of preservation (not creation) “does not rest in themselves … Rather they are God’s orders pf preservation, which have continued existence only as long as they remain open for the revelation in Christ.” Bonhoeffer is saying, life in Christ alone, and the discernment which takes place yherein, allows us to discern the orders, where they are pointing, what is good, what is evil. There is no such thing as pure “creation-based ethics.” It was this conviction (or at least one of them) that kept him from endorsing the German Volk as God’s ordained people, and the persecution of the Jewish people in the midst.

Bonhoeffer’s words spell out how it is only in Christ, his work in us and through us (“life and forgiveness”) that we can discern the goodness in creation and the ordinances that preserve creation. These “orders” must be open to Christ, Christ’s revelation, in order to discern what is of God and what is of sin. (He later worked this out in his Ethics via what he called the Divine Mandates).

I suggest that Bonhoeffer’s challenge has never been more important for the current challenges of our times. When it comes to all our moral judgements, our justifications for upholding government, a policy of government, a role for education, endorsing a particular cultural understandings of race, gender/sexuality, we all need to heed Bonhoeffer and the way “this is just the way things are created” works to ensconce power, brokenness, and even evil in our moral judgements and ways of life.

Bonhoeffer is a challenge to all of us in these times to discern together, through Scripture and a living submission to the presence and ongoing work of the Spirit in our lives, what is of God, the goodness of God’s creation, and what is of the evil one, the usurpation of worldly power to do things in the name of God. We must see Jesus.

Has this been helpful? Questions/comments will be responded to.

Yes. Discernment comes when we recognize that Creation was made good, and also Creation is fallen. So everything is tainted by Sin, and we need the Spirit of Jesus to distinguish between what is truly good and what is a consequence of the fall. Another substack I read this morning was talking about sanctification, the process of becoming a disciple that embodies what it looks like to follow Jesus, and I believe that’s what is desperately needed in the American church.

David, I appreciate what you're saying, and agree with you on much of it. However, your assessment of the Dutch Calvinistic paradigm suffers from oversimplification. Shalom to you and your good work!