“I Prefer Not To”

A Strategy for Resisting the Cultural Pressures that Undercut Mission in America

(I’m taking a break on the Bonhoeffer series to write this piece. I’ll be back in a few weeks with another post on “Bonhoeffer- A Person for our Times - I have 2 more to go).

There is a pressure that young people in mainstream America face upon graduating from college. Get married, get the secure job, buy a house, have 2.5 kids, and then spend the majority of your life keeping up with that lifestyle. Keep working and ascend the proper rungs on the ladder. By the time you’re 50 years old, your kids are out of college, and a huge chunk of your life has been swallowed up in the black whole of the American dream, maybe now you can think about ministry/mission?

I have had hundreds of people talk to me about these pressures over the years. From a 20 year old to a 50 year old, most all Americans face these pressures (the exceptions are immigrants, who often work hard just to survive and offer their children this ‘dream life’ of America). Once I had about a dozen young future missional leaders over to my house to talk about life and mission. Many talked openly about the fear of the lack of security in the missional pastor/church planter life (I pulled it out of them). It would be much easier, it seemed, to go the more secure route and do the typical pastoral route in order to ascend to the position of a professional senior pastor with full salary and benefits.

It is the default mode in American society to attach one’s identity to a certain version of success. We judge our lives, attach happiness to a.) being successful in career, b.) having the basic comforts of status and provision, c.) have a family. It was once the case that most pastors coming out of seminary, with professional degrees, attached their identity to their career success in their churches. How fast were they able to grow it? How many conversions? How many books did they write. How successful were they at managing the growth of this church into a mega/influential church.

All of these pressures work against the missional verve for every Christian. If we give in, inevitably our energy gets focused elsewhere. Church turns into a few hours of volunteer work a week. We get sucked in and compromise, our lives become busy, we must work 60 hours a week, we must spend countless hours making up for our absence from our families. Church becomes this side activity which we take on to get the warm fuzzy comforts of being spiritually secure – and to support the vacuity of this same lifestyle (and to provide our children with a good Christian education). Living the Christian life becomes a sub-therapeutic accoutrement we take on to balance the pressures/demands of the American consumerist/capitalist/Focus on the Family kind of life. And of course most of our evangelical churches find ways to make this feel alright.

Now I should say: I have no problem buying a house – when it is a ‘Kingdom discernment.’ I have no problem having children when we do not make our children into idols for our own self identity, self-glorying (and please - let us also elevate celibacy as a noble standard for Christian mission). We raise children for the Kingdom unto God’s glory not our own. I have no problem even when a career is blessed by God in wealth – when this wealth and success come as a surprise (in other words our goal was to do the job for God’s glory not our own wealth accumulation) and when this wealth is seen as God’s and used for His Kingdom.

But we need a way of seeing and living that even begins to make this alternative life possible. We must cultivate an appetite and a vision for another way of life. To do this we will need a posture of resistance to the American consumerist dream.

Bartleby’s “I Prefer Not To”

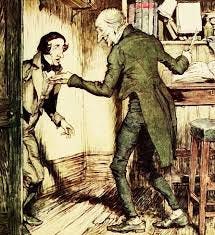

The cultural theorist Zizek, in his book The Parrallax View, points to Herman Melville’s character Bartleby (in Melville’s short story Bartleby, the Scrivener: a Story of Wall Street) who began to challenge the demands of his office where he worked with the phrase “Thank-you, but I prefer not to.” Each time the boss would ask Bartleby to do a menial task (make copies etc), Bartleby, who was hired as the “copy boy,” would say “thank-you, but I prefer not to” (the heading picture of this post is Bartleby tking a direction from his boss). His genial way, offered with a generous smile and a thank-you, disarmed his superiors. He was questioning the order of things, refusing to participate in it, in a way which made it difficult for the ones in power to fire him. But he also could not be ignored.

For Zizek this phrase is a gesture that provides the posture for a resistance to an all pervasive ideology that seeks to absorb anything we say or do into its own ways. Paraphrasing Zizek, we can imagine the varieties of such a gesture in today’s public space: … There are great chances of a new career here! Join us!” “Thank-you but I would prefer not to.” You must get married in order to have children, and a retirement, or you will have nothing to live for - “Thank-you but I prefer not to.” You haven’t bought a house? You’re wasting your money. Throwing it down the drain in rent - “Thank-you but I prefer not to.” Zizek says this is more than the kind of resistance which parasites upon what it negates (we must bring justice to the minority peoples who have been excluded from our economic prosperity! Yes, let’s make it possible to sell them houses they can’t afford too!”) This is a resistance which opens up a new space, to live differently, outside of the hegemonic culture.”(383-384)

Space doesn’t allow me to explain all of what Zizek is doing here. And Bartleby of course ended up opting out of society as a whole, which is not what Christians aim for. But what we can focus on with the lesson of Bartleby, is how the people were stunned by Bartleby’s posture of refusal to play the games of the politics of his office and society, and yet they could not be offended by the refusal at the same time. They were just kind of stopped in their tracks, asking, why is this person this way? They were led to reflection.

I also suggest that Bartleby himself was changed. He became more of what he was leaning into. This is not to say Bartleby wouldn’t buy a house or a car, but it might be a 3 bedroom house not a 4 or even 5, or a Honda CRV (hybrid) that runs for 10 years without a major repair bill instead of a $90,000 Mercedes. And each time he drives past that luxury mansion, he doesn’t get squirrelly, he says “huh, I prefer not to.” He sees that 90,000 Mercedes on the highway, he gives it a nod, and says “thank-you Lord for this CRV, and oh, I prefer not to.” Slowly our postures take root in contentment, as we give of ourselves to the riches of the Kingdom, the relationships, the ways that drive us to lead the lives we do. All of this leads to a different set of blessings.

The Tactic Will Spread

Once we learn how to gesture in this way – the “thank-you I prefer not to” can spread into other areas of cultural pressures and injustices. Our lives, our churches can become the means to disrupt the ideologies that run so deep in the ways of American life. We can become the wrench in the ideological machines of our time, making people pause, take notice, reflect a little and say, “you know what, thank you but I prefer not too as well.”

When the ICE agent comes to the door of a school, hospital, church seeking out immigrants to arrest – “thank you, but I prefer not to.” Say it with a smile. When the emails come from DOGE requesting an answer to 5 things you’ve done this past week, send a form letter with 5 generic things and in doing so, you’re saying, ‘thank-you, I prefer not to.” And oh, offer a helpful suggestion, maybe Elon should send this letter to the US Congress as well.

For sure, this won’t help when that Medicade check doesn’t come. For sure we will have to resort to other means, and do more ambitious resistance, for the many injustices around us. But folks, “Thank-you, but I prefer not to” is a tactic meant to shape a disruption. It’s part of living a life differently to resist the ideologies swirling around us. It can be a stunning means to stick a wrench into the machinery of this mess we find ourselves in.

In the words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in his famous ‘The Church and the Jewish Question,’ let us “not just bind up the wounds of the victims beneath the wheel but fall into the spokes of the wheel itself.” (trans by Mark Thiessen Nation, Discipleship, p. 32). Let us be the wrench stuck in the wheels of the machinery of injustice that brings its turning to halt. It is the way of non-violence, presence, peaceful resistance. And God shall use this space to disrupt the evil powers, and expose their lies. “And He shall reign until all evil has been made subject” (1 Cor 15:25).

Good stuff. I just got back from a mission trip to Nepal where churches of 60-80 are planting churches at an astounding rate and producing called pastors to lead them. In reflecting on why these churches are outstripping their US counterparts 10 to 1, a lot of thoughts came to mind, but one factor for from a human perspective was the lack of security all around. The equation wasn't- "Should I take a six figure salary and enjoy the good life OR should I scrimp and struggle as a church planter?" It was: Well, I can be under employed and poor apart from the kingdom of God or "I can be poor while being faithful to God and his kingdom." It's a lot easier to say "I prefer not" when the options are equalized.