BONHOEFFER A PERSON FOR OUR TIMES (Post 4)

His Relenting Push for an Authentic Church in Nazi Germany

Warning: This post gets into the deep weeds of Christian theological ethics and formation.

This is the 4th of 5 posts on ‘Fitch’s Provocations’ addressing Bonhoeffer’s theology for our times.

In previous posts I examined the role of Jesus (Christology) and creation in Bonhoeffer’s ethics (those posts are found HERE and HERE). These posts examine the way our Christian witness/character is formed by our theology of “who Jesus is” and “creation.” Bonhoeffer helps us see how these beliefs, and the practices formed in/by these beliefs, shape our moral lives in the world. In Bonhoeffer’s case, they shaped him for unrelenting witness to Jesus amidst the Nazis even unto death. In the same way, Bonhoeffer’s theology can shape us for the ideological times we live in.

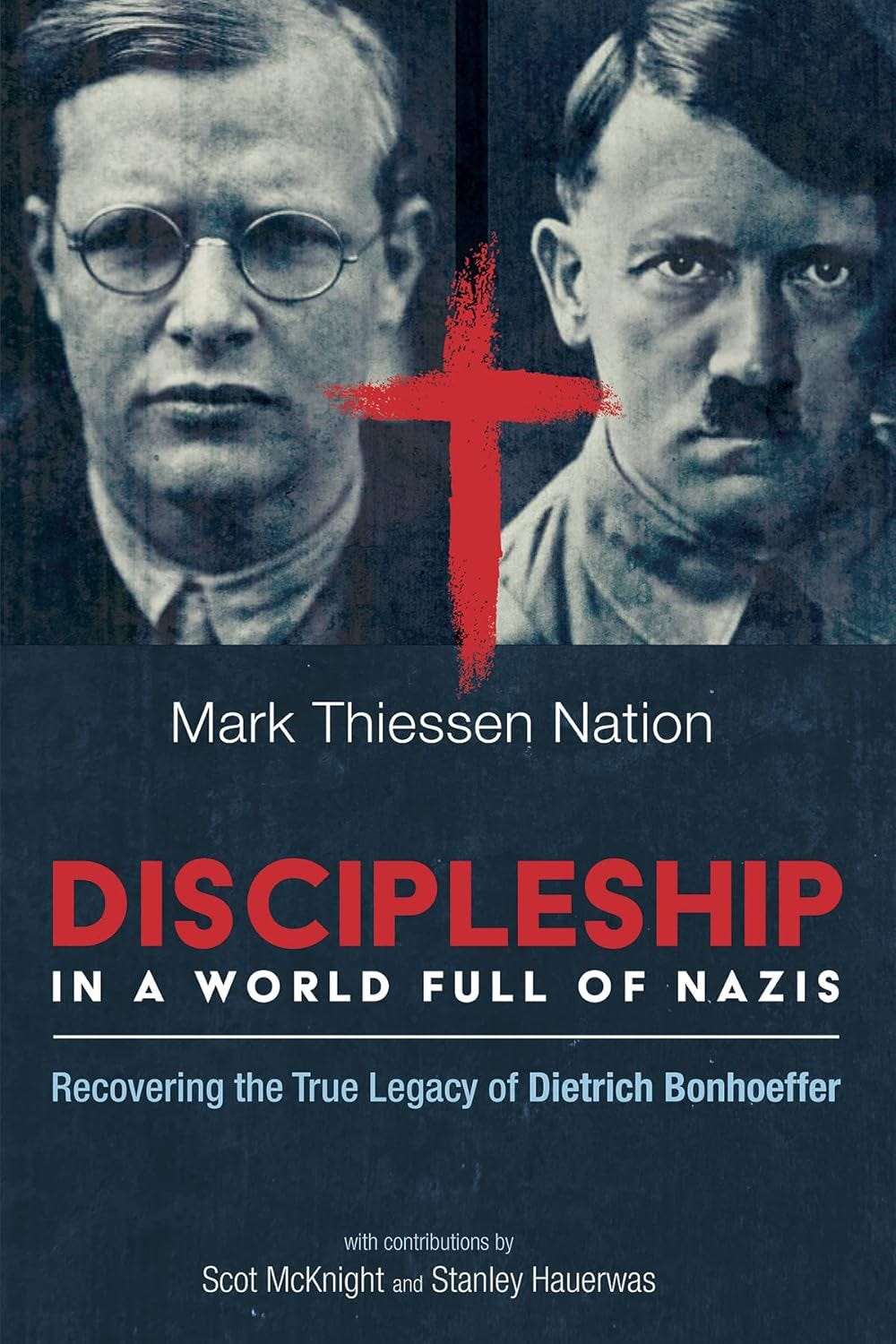

I’m drawing almost entirely from Mark Thiessen Nation’s (heretofore referred to as MTN) book Discipleship in a World Full of Nazis (pages numbers in parentheses) which traces Bonhoeffer’s theology alongside the events of his life. It’s a powerful exploration of how theology forms a life of witness. After reading it, I’m convinced if there’d been a few thousand more Bonhoeffers as pastors and a few thousand more Finkenwaldes (the learning community Bonhoeffer planted) in Germany in the thirties, Hitler never would have happened. Perhaps the same can be true for our time?

In this post I want to engage Bonhoeffer’s view of the church, and its role in engaging the injustices of the world. Bonhoeffer’s ecclesiology shaped his life and discipleship.

The Church and State According to Later German Lutheranism

The first thing to say here is that Bonhoeffer was a Lutheran, and carried with him aspects of his Lutheranism into his theology of the church’s relation to the state. For Luther, there were two kingdoms, governed by the two hands of God: the left hand of the sword, governing the world through coercion, and the right hand of the Spirit, governing the world through the conviction and presence of the Spirit. For most church people in 1930’s Germany, under the influence of this late 19th cent. Lutheranism, and Luther’s challenge that never shall the two kingdoms mix, they believed the state was to be left to do its job tending to the civil affairs of material life, and the church was to stay in its lane, doing its job of tending to the spiritual souls of men and women. And never shall the two interfere with one another.

In Bonhoeffer’s essay ‘The Church and the Jewish Question’ (1933) (already referred to in this series), there’s evidence Bonhoeffer retains this Lutheran influence. He asserts that the church should refrain from “any moralizing” regarding specific behaviors by the state” (MTN p.31). He states that “the Reformation’s view of the church is to refrain from any direct involvement in political actions of the state. The state is acting as “God’s order of preservation” “in the midst of world’s chaotic godlessness.” As such, the state is there to preserve the world from chaos due its sinful state.

And so Bonhoeffer is adhering to some of the current German Lutheran view of the church-state relation playing off the two kingdoms doctrine of Luther and the separation of the two powers, the left hand and the right hand of God.

Bonhoeffer Maintains The Church/State Distinction

MTN however describes how this adherence does not mean for Bonhoeffer that “the church stands aside, indifferent to” the political actions of the state. Indeed, in the same 1933 essay, Bonhoeffer outlines three courses of action for the church that faces injustice at the hands of the state. The church can 1.) Question the state as to the legitimacy of its actions, 2.) Be of service to the victim’s of the state’s actions, and 3.), in regard to the moving wheel of the state, “not just bind up the wounds of the victims beneath the wheel but to fall into the spokes of the wheel itself.” (p. 32). All of these options, for Bonhoeffer, still qualify as indirect political action on the part of the church.

In the ensuing ten years, Bonhoeffer works hard to keep the German protestant church distinct from the state, to keep it from becoming subsumed as a part of the Nazi state, to maintain the church as a separate voice with it’s allegiance solely to Christ and the word of God. He helps lead the ‘Confessing Church movement,’ a movement of pastors dissenting from the German Christian church who had become absorbed by the Nazi state. He worked tirelessly underground to record the state acts of violence, the deporting of Jews to concentration camps, and other injustices to insure that somehow these acts would not go unseen and that the state would be held accountable. (p. 44,45)

The Lutheran impulse of the German church of that day, many argue, was to diligently separate the two powers (Kingdoms), the power of the state to preserve society through force, from the power of the church through the Spirit to heal and transform souls. Each was to keep to their own calling. The church was to give the state its blessing to fulfill its call and thereby it went passive towards the state. The church blessed the state, even the Nazi state, to do what it must do to preserve society as ordained from God. And so Hitler was allowed and even blessed to run the state as he saw fit and received the allegiance of the German people for doing so (for more on this, see my book Reckoning with Power p. 82 on this, as well as how Romans 13 was used on p.93-97, as well as the footnotes for each of these pages). The church was to stay out of the state’s way. Many put forth the so-called “Luther to Hitler” hypothesis to this day, that this kind of ‘Lutheranism’ led post-World War One Germany to accommodate Hitler and attribute the rise of Hitler to God’s work.

But Bonhoeffer said “no” to this kind of passivity. He led a way for the German church to be a witness against the state all the while preserving the distinction between the call, power and role of the state versus the call, power and role of church.

Bonhoeffer for this Cultural Moment

There are lessons here in Bonhoeffer’s theology for our current cultural moment. The church in the U.S. is continually tempted to the extremes on the church/state relation issue. Today’s church (especially the evangelical church) either opts for a church-less Passivity or a church-less Activism. It goes hyper-Passive as it sees the state as a functioning order of preservation in the world, not to be interfered with by the church: i.e. just let people vote their conscience. OR It goes hyper-Activist as it sees the state as the only way to impact culture and society for justice. Therefore the church must throw all its marbles in on getting the state to work rightly for the justice of society. In the process the hyper-Activist abnegates the church’s own distinct role as the church in the world doing justice under the power and presence of Jesus. The church becomes merely a volunteer training organization for the state. Evangelicals (fundamentalists) and post-evangelicals lapse often into one of these two options

Bonhoeffer says “no” to either option. The church must maintain its own identity in Christ as a space of witness for the justice of God. It must corporately embody this justice in its own way of life to resist the powers of the state when it goes off the rails. For sure it can send Christians to the state to take up roles, but in the process the church must not give up its calling to be the presence of Christ in the culture. And it is out this space, that the church, confronts, engages and witnesses directly to the state, especially when it does not live up to its own calling under the ordinance of God.

In this cultural moment, if the church is not to be absorbed into the state (Christian Nationalism), if it is not to sit idly by allowing the state to do its work without accountability, it first must be a people, who live in integrity and faithfulness to being a community of justice, righteousness, holiness, out of its one allegiance to Jesus Christ our Lord.

A Search for the True (Real) Church of the Risen Christ

This brings me to the most important point for Bonhoeffer’s ecclesiological convictions and formation: Despite the failures of the German church amidst Nazi Germany, Bonhoeffer doubled down seeking the authentic church. For Bonhoeffer there was no other way to resist Hitler than the embodied social witness of another rule: the rule and reign of Jesus Christ.

You could say, it started with Bonhoeffer’s first dissertation, written at the age of 21, entitled Sanctorum Communio (Community of Saints 1927). It was a dissertation drawing on the famous work of Troelsch, describing the church as an institution/body in society. Yet Bonhoeffer was already showing influence from his new-found relationship with Karl Barth, arguing against a church that merely functions as an (human)institution in history alongside other institutions within a sociology. For Bonhoeffer, the church is a sociology unto itself, a redeemed transformed social reality as the presence of Christ in the world. Hauerwas has said (in a podcast) that “Bonhoeffer’s Sanctorum Communio freed the church from Troelsch.”

For the rest of his life, Bonhoeffer never really wavered from his focus on the church as a body of Christ’s presence in the world. The German church of the 30’s had become a cultural entity/religion absorbed within the German Volk functioning as a buttress to it. Bonhoeffer saw that the church must be freed from its captivity to the bourgeois German culture in order to become the prophetic and real presence of Jesus the Christ in the culture itself.

Bonhoeffer returned from NYC in 1931, after his experience at the Abyssinian Baptist church, to give a sober assessment of the state of the church in Germany in a letter written to a friend. He mourned that “Invisibility is ruining us …” We (Germans) need to see “that Christ has been here.” (MTN 153). This lack of a church body living the presence of the living Christ in the face of evil , fear and fascism, plagued him all the way to his final days in prison.

In 1932, Bonhoeffer addresses the International Youth Conference in Switzerland, and his opening words are “The Church is dead” and then he reminds them that “God raises the dead” (MTN 69-70). He says the church can only be vibrant and life-giving if Christ is at its center. In the world (of 1930’s/40’s Germany) filled with “political extremes against political extremes,” full of distrust and suspicion, where “the demons themselves have taken control of the world …”, there can be no change by merely offering better education, more international understanding. (MTN 70) No, “Christ alone adjures the false gods and demons.” And so the church must return to being the presence of Jesus living in and among us, dismantling these powers for Christ’s peace.

In a 1944 letter written to a friend from prison, he asks “how can Christ become Lord of the religionless?,” those who have not succumbed to the cultural bourgeois Christianity of Germany. He chastens his mentor Barth saying, “Barth, who is the only one to have begun thinking along these lines, nevertheless did not pursue these thoughts all the way … the question to be answered would be: What does a church, a congregation, a sermon, a liturgy, a Christian life, mean in a religionless world?” (On Barth’s ecclesiology and its incompleteness I recommend Bender’s book HERE). Bonhoeffer is desperately asking how the church can escape from a cultural religion to becoming the real embodied presence of the Christ who has died and is risen among a culture gone awry, and a church so absorbed by lifeless powerless cultural religion.

The community at Finkenwalde was eventually Bonhoeffer’s answer to these questions. The current state of the German church drove him finally to start a community at Finkenwalde, a seminary community for the training of pastors into a way of being in the presence of Christ that can resist the world of evil, and yet give a compelling witness to another way. He saw the embodied presence of the church as the only true means of resistance to the ideological evil that had taken over the German world. And so this conviction led him to Finkenwalde, and a life together with other Christians, from which he penned the book now titled Life Together. At a time when the German church was failing him massively in 1930’s/40’s Germany, Bonhoeffer did not desert it, he doubled down. He rejected a cultural religion church, for a truer embodied practice of Christ together at Finkenwalde.

Bonhoeffer for This Same Cultural Moment

And so here we stand, at this same cultural moment with Bonhoeffer: thousands, if not millions, ringing their hands of a church absorbed into cultural politics and cultural accommodations of assorted kinds, thousands, if not millions, making “deals with the devil” in the hopes of saving a Christian culture from demise by linking arms with the state, all of it steeped in utter corruption. AND YET Bonhoeffer did not retreat. Instead he started a community, a church, to eat together, study together, pray together and support one another together. It is in the end what sustained him unto death in allegiance to Christ. Perhaps it was too late. But I cannot help but wonder, if there had been a thousand Finkenwaldes in early thirties Germany, would Hitler even have happened? Would a world war been resisted? Who knows what else God could have done. May we all learn from and follow in the steps of Bonhoeffer. In Jesus’ name.

----------------

I have one more post on Bonhoeffer. How did his personal piety sustain him and strengthen him for witness against Hitler. If you’re interested, subscribe (for free). You’ll be notified when it hits.

Thank you David for this series. Since Bohoeffer was most sensitive to Jews, yet I feel he would have benefitted from certain dialogs that were perhaps not avaible to him. It never escapes me that he suffered the same martyrdom. He was still a product of theological Edom. In many ways it provided the biblical language you extracted out of your philosophical and post-liberal method which I have also walked. Thus I frame this Torat Edom Response: Restoring the Witness of the Redeemed Assembly

Bonhoeffer’s yearning for a community like Finkenwalde—a visible body of believers formed in obedience to Christ, standing against ideological capture—is precisely what Torat Edom names as the restored qahal and edah: not merely a “church,” but a gathered people under covenant, who live out the testimony (edut) of the Most High in the midst of corrupt empires. The terms qahal and edah are not incidental. In Hebrew Scripture, qahal is the assembly convened before the Lord, often linked to Sinai or moments of covenant renewal. Edah is the community of testimony, the collective that bears witness to God’s justice, especially when the ruling powers distort or suppress that justice.

Bonhoeffer, knowingly or not, reached back into this biblical vision. His work at Finkenwalde was not an institutional reform effort—it was a return to covenantal edut in the face of national apostasy. He sought a visible, lived testimony in a world overtaken by the principalities.

The Torat Edom view strengthens this by adding: This testimony must also include Esau. It must also include those who were historically excluded from the Abrahamic promise because of the church’s distortion of covenant through Rome.

No Christ Without the Wound—No Witness Without the Wounded Brother

Bonhoeffer’s ecclesiology was forged in suffering, and for this reason, Torat Edom sees in him a “redeemed brother” figure. In our terms, he bore the wound of the covenant. This aligns with the fundamental premise of Torat Edom: there is no gospel without the wound—without Jacob facing Esau, without Israel accounting for Edom, without Christ standing in the place of both victim and estranged brother.

Bonhoeffer’s embodied resistance was not a political activism, nor a cultural retreat. It was a covenantal response to betrayal—betrayal by the German church, which had forgotten the face of its brother. The Confessing Church was not only a resistance to Nazism, but a protest against the anti-witness of a church that had forgotten the gospel’s root in Jewish covenant, and thus its call to love the stranger, protect the vulnerable, and renounce empire.

In this sense, a Torat Edom ecclesiology would say:

The true qahal cannot emerge unless it includes the wounded—the rejected, the Edomite, the Nazarene, the Arab, the Jew, the Other—gathered not under nationalism or ideology, but under the mercy and justice of God.

Bonhoeffer’s Vision and the Noahide Mandate

The Torat Edom framework affirms Bonhoeffer’s commitment to a visible, embodied community living under the lordship of Christ—but reframes this not as an ecclesial abstraction, but as the extension of the Noahide mandate. The edah must be visibly righteous because it reflects the basic principles given to all humanity: justice, mercy, truth, rejection of idolatry, refusal to shed innocent blood. Bonhoeffer’s underground seminary was, in a way, a restored Noahide community within an apostate civilization—and this is what the church must become again.

We do not need a thousand more seminaries—we need a thousand more edot (witnessing communities) formed around chokhmah (wisdom), tzedakah (justice), chesed (covenantal loyalty), and emeth (truth). These cannot be built by political alliances or synodical declarations. They are formed where people break bread, study Torah, and name Christ as Sar haPanim—the one in whose face we meet the presence of God.

Rejecting Passive Pietism and Activist Idolatry Alike

Bonhoeffer’s critique of the false Lutheran dualism—the one that separated the sword from the Spirit and blessed the state unconditionally—is matched today by a church either paralyzed by neutrality or enthralled by power. Torat Edom critiques both. It says:

Passive pietism is a form of covenantal betrayal. To ignore the cries of the afflicted is to defile the Name.

Activist idolatry is no better. To seek justice without holiness, to merge the church into the machinery of the state, is to recreate the Tower of Babel in the name of righteousness.

Bonhoeffer knew this. His resistance was not about activism, but about formation—the slow, costly process of forming a qahal that resists both collaboration and compromise. Torat Edom insists the same: the only way forward is to build communities that embody the covenant—not as reaction, but as re-creation.

The Real Church Is the Remnant That Holds the Memory of the Brother

When Bonhoeffer mourned the “invisibility” of the church in Germany, he was mourning the loss of testimony. Torat Edom would sharpen this: he was mourning the loss of the brother. The church had not only become invisible, it had forgotten the story—the story of Jacob and Esau, of Joseph and his brothers, of Jesus and the rejected stone. A church that forgets its rejected brother cannot bear witness to the risen Christ.

The only true edah is the one that remembers. It remembers the covenant. It remembers the wound. It remembers the brothers it has cast off. It remembers that the church is not a substitute for Israel, but a servant to the nations and a witness to the mercy of God.

Bonhoeffer as a Precursor of Torat Edom

Ultimately, Bonhoeffer stands not just as a Christian martyr, but as a precursor of what Torat Edom calls a redeemed Edomite witness—one who, like Obadiah foretells, comes down from the heights of pride to join the house of Jacob in restoring the kingdom of the LORD (Obadiah 1:21). His cry for a religionless Christianity is a cry for a post-Constantinian qahal, a holy people formed not by culture or custom but by covenant and presence.

Building Finkenwaldes Today

In our moment, we are called not just to admire Bonhoeffer, but to become builders of Finkenwaldes—spaces of justice, fidelity, and prayer in a world of betrayal. Let us raise up edot in our cities, qahalot in our neighborhoods, and remember again: the gospel is not an idea, nor is the church a program. It is the presence of God in the midst of a world that has forgotten its brother. And where the brother is restored, the wound is healed.

That is the witness of Torat Edom.

That is the hope of the qahal.

That is the call of our time.

Ahhhh, Fitch, I would gladly join up with a modern-day Finkenwald, or even try to start one, but alas, I am no Bonhoeffer.... I am a pastor, trying to keep the call of Jesus before my congregation, who seem to relish the siren-call of pseudo-power of the Republican Party. "My Christians, my beautiful Christians!"... He's speaking our language... And frankly, Jesus seems to be loosing this round. I seriously wish I knew what to do... Dan Steinhart